In a previous post, we discussed how it came to be that the rules of the rules-based system reflect the philosophy of Milton Friedman, not John Maynard Keynes. Today, even as

- the business community feels obliged to at least look as though it is distancing itself from the Milton Friedman regime;

- the Financial Times editorial board says we need radical reforms to the economic policies of the past four decades; and

- the Pope rejects neoliberal laissez-faire economics

the trade community continues to prioritize enforcing these flawed rules above changing them.

Keynes’ thinking on economics had to do with democracy and stability. There’s a reason the pendulum is swinging back his way.

L’Etat, C’Est le WTO

Much of the current ideation of the dispute settlement system seems driven by a visceral, negative reaction toward the way the Trump Administration has approached the issue, even as many acknowledge that the U.S. grievances predate him by a decade. But it does not follow that just because Trump tramples norms, the answer is to restore the Appellate Body function the minute Trump is out of office.

In fact, the elevation of dispute settlement over respect for Member sovereignty is at odds with the vision of the founders of the system – that is, the people credited with creating the rules-based order itself. The founders did not think dispute settlement was more important than a Member’s own sovereignty. Just the opposite: they created an expedited mechanism for leaving the institution if a Member didn’t agree with a dispute settlement outcome.

The priority for the founders of the system – including Keynes – was not multilateralism for its own sake. It was multilateralism in service of democracy, through economic stability and free enterprise. The notion that an institution would be more important than a country’s assessment of its own security interests would baffle them.

The founders rejected laissez-faire economics as the basis for the global trading system. They also rejected non-market economics as a basis for trading, believing it would ultimately destroy democracy. Yet what we have today is a laissez-faire system that has facilitated the rise of a state trading autocracy so economically powerful that it can export authoritarianism. In other words, the WTO system, with China in it, has created exactly the situation the founders, who had tangled with an imperialist fascist or two, feared.

When the United States began ringing the alarm bells over WTO dispute settlement 15 years ago, other Members responded by tsk-ing the Americans for daring to criticize The Institution. The Institution was, by definition, above reproach. That attitude is precisely why the Appellate Body felt emboldened to do what it liked, instead of respecting the outcomes negotiated by Members. As former Appellate Body Member Ricardo Ramírez Hernàndez explained,

It seems to me that the crisis we now face could have been avoided if it had been addressed head-on, as it began to escalate. The WTO is a consensus-based collective. This means that this crisis should not be attributed to one Member. The Membership must recognize the need for leadership within and outside this house. A need to recognize that there must be genuine engagement when one Member is raising problems.

Ironically, it is the Appellate Body that created its own existential threat by failing to respect the rules of the rules-based system.

The United States Isn’t Isolated on the AB

There is a widespread perception (particularly in the American foreign policy community) that the U.S. government is alone in doubting the utility of the Appellate Body.

The facts suggest otherwise. Most WTO members have not signed up for the EU’s alt-Appellate Body mechanism. Among the major holdouts: Japan, India, and Korea — all countries that are in China’s neighborhood. Maybe they’re aware that, according to a report issued by Jeff Kucik of the University of Arizona, China has a higher compliance rate at the WTO than the United States, Europe, and Japan — and that this reality exposes the superficiality of the notion that the dispute settlement system promotes genuine compliance with the rules-based system.

We Did Just Fine Before

We’ve been led to believe that trade agreements without binding dispute settlement mechanisms are useless. But that view is fundamentally inconsistent with history. The GATT didn’t have binding dispute settlement. Does that mean the GATT was pointless? The U.S.-Israel Trade Agreement doesn’t have binding dispute settlement. Does that mean it’s pointless? It’s been in place for nearly 40 years.

Arguing that the WTO dispute settlement system is the crown jewel of the organization seems more like an indictment than an endorsement. This Portman/Cardin resolution points out that the WTO has become too focused on litigation, and not focused enough on negotiation.

The unfortunate outcome, where litigation poisons negotiations, shouldn’t come as a surprise. Scholars warned of it, predicting that a litigious dispute settlement system would engender acrimony and undermine more cooperative undertakings. As noted scholar William Davey explained in 1987

Critics of the adjudication model claim that it will promote conflict and contentiousness in an organization that must promote negotiated solutions to achieve its goals.

Their concerns have been validated, as the WTO struggles to move forward on negotiations. Yet this report from the Center for American Progress emphasizes the urgency of substantive reforms to WTO rules to ensure that the system promotes such priorities as inclusive growth. Why would we fix the dispute settlement system before we fix the rules? China has already rejected overtures to fix the subsidy rules. Enforcement of the existing regime suits China perfectly.

Should Seven Bureaucrats in Geneva Decide if Joe Biden Gets to Be Transformational?

This all matters for Joe Biden, if he wins. He’ll be pressured to correct for Trump’s norm-trampling, and immediately get back to appointing Appellate Body Members.

Would that be in Biden’s interest? Two of his signature domestic priorities are addressing climate change and restoring our domestic manufacturing capabilities. Although nobody wants to talk about it, the reality is that executing these strategies would most likely require policy space the WTO dispute settlement system – oriented as it is toward laissez-faire economics — hasn’t proven itself capable of tolerating. It’s part of the reason CAP has emphasized the kinds of substantive reforms WTO Members have to embrace.

The WTO believes its fundamental purpose is increasing trade flows. That, coupled with the laissez-faire orientation of the rules, means that if a Member regulates in a way that impedes trade flows, the WTO is likely to find against it.

Let’s look at the WTO’s record on the environment, a priority for Biden. Some will argue that Members can adopt carbon border taxes consistent with WTO rules. Great! But it doesn’t matter what anyone thinks, other than the Appellate Body. And what the Appellate Body has thought so far isn’t encouraging.

In the famous Shrimp Turtle dispute, the United States sought to ensure that countries exporting shrimp to the United States adhered to the same rules as domestic producers of shrimp, to minimize incidental turtle catches. In rejecting a U.S. undertaking designed not to discriminate against imports, the Appellate Body faulted it for just that reason, accusing the United States of imposing unilateral rules for access to its own market. As the Appellate Body explained, the unilateral nature of the U.S. effort to limit turtle deaths “heightens the disruptive and discriminatory influence . . . and underscores its unjustifiability.” (para 172)

This is the embodiment of the modern global trading regime – elevating multilateralism itself over and above solving real and pressing problems. Requiring multilateral negotiations to solve environmental problems, and removing policy space to act unilaterally, leads to a lowest-common denominator approach to sustainable development. The planet can’t afford it.

In a bold PR effort, the WTO has a page on its website devoted to the issue of trade and the environment. This is the spin on Shrimp Turtle: “the WTO pushed members towards a strengthening of their environmental collaboration; it required that a cooperative environmental solution be sought for the protection of sea turtles between the parties to the conflict.” What they leave out, of course, is that they struck the U.S. measure down. The decision was not about environmentalism, but about multilateralism.

And note that the WTO says it “pushed,” and “required” a cooperative environmental solution. Not that the WTO agreements require it (they don’t) – the WTO itself required it. This is where the WTO says the quiet part out loud: it is not an institution executing Members’ agreements. It is an institution that tells Members what to do. L’état, c’est moi.

The only dispute the WTO itself references in support of the environment is one that isn’t even on the environment. It’s on human health. The organization pats itself on the back because the dispute settlement system “allowed a member in 2001 to maintain its ban on the importation of asbestos so it could protect its citizens and construction workers.” The WTO expects accolades for “allowing” a country to ban imports of asbestos! Welcome to the 1970s.

But even on human health, the Appellate Body’s record is dubious. The United States had the temerity to regulate clove cigarettes because they were found to be a gateway for teen smoking. The Appellate Body explained that the purpose of the regulation – addressing teen smoking – is less important than assessing the competitive relationship between the products under consideration (clove and menthol cigarettes). (paras. 112, 116, 136). The Appellate Body went on to state that

At the same time, the mere fact that clove cigarettes are smoked disproportionately by youth, while menthol cigarettes are smoked more evenly by young and adult smokers does not necessarily affect the degree of substitutability between clove and menthol cigarettes. (Para. 144)

The “mere fact!” For the Appellate Body, it’s as if these cigarettes are being smoked by robots rather than kids.

If you are a normal person, i.e., not a trade lawyer, you could be forgiven for reading this kind of decision and wondering whether there is a soupçon of sociopathy coursing through the system’s veins.

But We Win Every Case We Bring!

There is, of course, the argument that the United States wins every dispute it brings at the WTO. The problem is, so does just about everyone else. And the United States is the most frequently sued WTO Member. The math is not on our side.

That the United States is the most sued has less to do with whether the United States is some rampant scofflaw (the United States did take seriously executing its Uruguay Round commitments) than whether other WTO Members have chosen to use the dispute settlement system to achieve that which they could not get at the negotiating table. This propensity underpins the U.S. complaints, across three administrations, over the operation of the dispute settlement system.

And it’s not just trade remedies, which is often the way the problem is framed, though certainly WTO decisions making it harder to address Chinese subsidies are deeply problematic. But it’s agriculture, too. In Cotton, the Appellate Body blew through the “peace clause,” which was supposed to preclude the litigation itself. If you add in decisions on teen smoking and gambling, the WTO starts to look like a regular den of iniquity. Here’s where it’s once again worth recalling who is defending the Appellate Body the most vigorously – libertarian groups such as the Cato Institute and Americans for Prosperity.

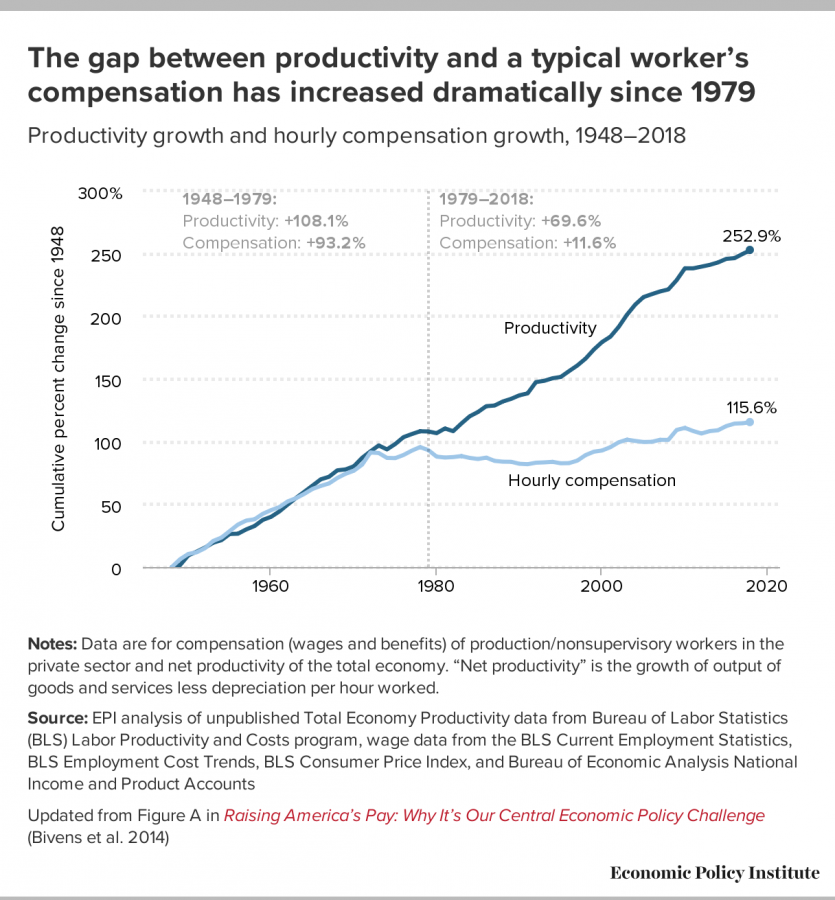

Focusing on offensive victories instead of defensive losses prioritizes exports (opening foreign markets) over domestic production (trade remedies protect our manufacturing base). This set of priorities has dominated Executive Branch trade policies for decades. Look at the results of the Tokyo Round negotiations, which concluded in 1979. Congress instructed the Executive Branch to negotiate labor standards at the GATT, and the Carter Administration came home with disciplines on trade remedies instead. Lose-lose for American manufacturing workers, who, as a result, not only have had to compete with exploitative labor conditions abroad, but have watched their ability to protect the domestic market against unfair competition get watered down. And watered down not just by the rules themselves, but by the WTO’s hostility to trade remedies. The results?

Today, the United States is paying a heavy price for its choices, and not just in disaffection among blue-collar workers. The chase for exports, coupled with the glib view that manufacturing was something to be offshored, is precisely why our trade agreements have been structured to promote agriculture and offshore manufacturing. Now that COVID has shown us how important manufacturing is, the United States is trying to rejuvenate its industrial base.

We simply cannot return to the policies that put us in this predicament in the first place. We must put exports in their proper perspective. According to the Coalition for Prosperous America, the domestic market for manufactured goods is about $7 trillion. Exports of manufactured goods are $1.65 trillion. That illustrates the degree to which the domestic market for manufactured goods is more significant than the export market. According to USDA, American agricultural exports are valued at $140 billion – in other words, a fraction of the value of manufacturing exports, which are a fraction of the value of domestic demand. Add agricultural, manufacturing, and services exports together, and they contribute just 12% to GDP. Given the relative status of production for export and production for domestic consumption, the WTO losses are, arguably, of greater significance than the WTO victories.

Senator Josh Hawley, who seems to have 2024 ambitions, has already introduced a resolution for the United States to withdraw from the WTO. Rejoining the dispute settlement system absent true change invites a repeat in 2024 of the 2016 Presidential campaign, where trade proved to be a lightning rod. Frustration with the way globalization has been executed cost the incumbent party votes – maybe even decisive votes. This risk is only aggravated by the parallel push to revive U.S. participation in TPP – another 2016 campaign lightning rod.

Surely we have the capacity to create a trade policy that moves us forward, not backward.

We Do Owe it Our Trading Partners to Engage on the WTO

No, we don’t have to start appointing Appellate Body members as a mea culpa for Trump. At the same time, WTO Members have been exasperated at the lack of U.S. engagement on finding some path forward on dispute settlement.

The United States should engage. But let’s be sensible and strategic, instead of ideological and nostalgic. Rather than assuming that the starting point is “how do we save the Appellate Body because that’s what we did before and Trump was very rude” we should instead go back and revisit why we found the GATT procedures inadequate in the first place – and see if there are better ways of fixing the problem.

If we are clear-eyed in our assessment, we realize that the core flaw with the Appellate Body cannot be fixed. There is no rule that will contain an Appellate Body that does not believe it is bound by the rules to begin with. For years, other WTO Members made the Faustian bargain of looking the other way when the Appellate Body overreached. Demonstrably results-oriented, they cannot be trusted to discipline the Appellate Body, and thus any sort of oversight committee offers no assurances that the Appellate Body can be reined in.

The principal target of Appellate Body overreach has been the United States. This isn’t because the Appellate Body was anti-American – I don’t believe it was – but because Members wanted more access to the lucrative U.S. market than they were able to extract at the negotiating table, and the Appellate Body was all too willing to give it to them. No set of rules will change that fundamental dynamic.

For those Members who believe an Appellate Body is mandatory, carry on with the EU system.

For everyone else, let’s work together to devise a system we can trust.

And, more importantly, fix the rules of the rules-based system.

October 9, 2020