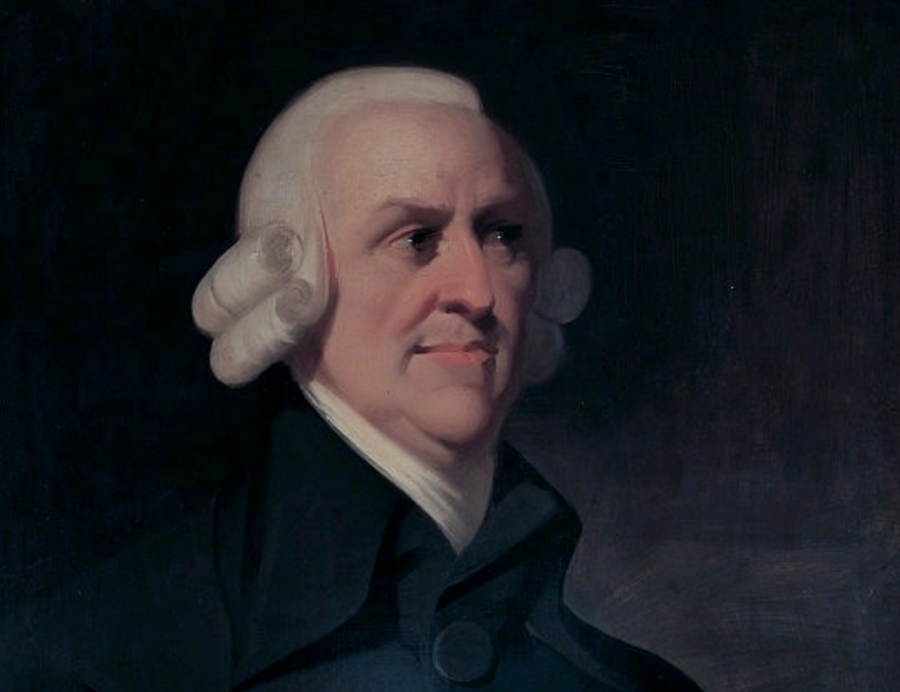

We think of Adam Smith as the father of free trade. Having coined the phrase “Invisible Hand,” he’s portrayed as something of a libertarian icon. But that’s a caricature of a man who had much more profound, and nuanced, views of political economy – and of the welfare of the working class.

Smith on Tariffs

Generally opposed to tariffs, Adam Smith didn’t object to them absolutely. For example, he thought they were important for preserving domestic production of goods essential to national security:

There seem, however, to be . . . cases in which it will generally be advantageous to lay some burden upon foreign for the encouragement of domestic industry. {One such case} is when some particular sort of industry is necessary for the defence of the country. (Modern Library Edition, 492)

He also thought tariffs could be useful in circumstances where reciprocity was lacking, such as

when some foreign nation restrains by high duties or prohibitions the importation of some of our manufactures into the country. (497)

He had doubts about how effective this approach would be, but those who don’t like the passage tend to present only half the story, making his doubts seem more absolute than they were.

So, the idea that Adam Smith was a free trade fundamentalist is not consistent with his own writings.

Smith on Monopolists

What Adam Smith really didn’t like was monopoly – and monopolists.

The capricious ambition of kings and ministers has not, during the present and the preceding century, been more fatal to the repose of Europe, than the impertinent jealousy of merchants and manufacturers. The violence and injustice of the rulers of mankind is an ancient evil, for which, I am afraid, the nature of human affairs can scarce admit of a remedy. But the mean rapacity, the monopolizing spirit of merchants and manufacturers, who neither are, nor ought to be, the rulers of mankind, though it cannot perhaps be corrected, may very easily be prevented from disturbing the tranquility of any body but themselves. (527)

He attributes some of the sins of mercantilism not just to bad government policy, but to the cupidity of monopolists. This is the root of Smith’s antipathy for tariffs. He sees tariffs as an extension of that cupidity:

it is the interest of the merchants and manufacturers of every country to secure to themselves the monopoly of the home market. Hence . . . the extraordinary duties upon almost all goods imported by alien merchants.”(527)

The effects of concentrated economic power on public policy were not lost on Smith. He describes the monopolies of his day as being akin to

an overgrown standing army . . . they have become formidable to the government, and upon many occasions intimidate the legislature. The member of parliament who supports every proposal for strengthening this monopoly, is sure to acquire not only the reputation of understanding trade, but great popularity and influence with an order of men whose numbers and wealth render them of great importance. If he opposes them, on the contrary, and still more if he has authority enough to be able to thwart them, neither the most acknowledged probity, nor the highest rank, nor the greatest public services, can protect him from the most infamous abuse and detraction, from personal insults, nor sometimes from real danger, arising from insolent outrage of furious and disappointed monopolists. (501-2)

In promoting freer trade, Smith cautions against allowing monopolists to benefit – or even creating new monopolies:

The legislature, were it possible that its deliberations could always be directed, not by the clamorous importunity of partial interests, but by an extensive view of the general good, ought upon this very account, perhaps, to be particularly careful neither to establish any new monopolies of this kind, nor to extend further those that are established. (502)

We repealed Glass-Steagall because we were told that our banks couldn’t compete globally otherwise. Welcome, Too Big To Fail, and its sidekick, Too Big to Jail. The same arguments – you have to be big to compete globally — are now being made with respect to Big Tech.

Smith on Wage Suppression

Smith also recognized that monopolists — indeed, owners of capital more broadly — crush labor.

Masters are always and every where in a sort of tacit, but constant and uniform combination, not to raise the wages of labour above the actual rate . . . . Masters too sometimes enter into particular combinations to sink the wages of labour even below this rate. (76)

Smith considered a decline in the condition of labor a sign of an ailing regime.

The liberal reward of labour, therefore, as it is the necessary effect, so it is the natural symptom of increasing national wealth. The scanty maintenance of the labouring poor, on the other hand, is the natural symptom that things are at a stand, and their starving condition that they are going fast backwards. (84)

Smith on Cross-Border Capital Flows

Critically, Smith assumed that capitalists would keep their capital at home:

{E}very individual endeavours to employ his capital as near home as he can, and consequently as much as he can in the support of domestic industry . . . . (482)

He goes on to argue that

every individual naturally inclines to employ his capital in the manner in which it is likely to afford the greatest support to domestic industry, and to give revenue and employment to the great number of people of his own country. (484)

* * *

So, to summarize: tariffs are not always bad; capitalists invest their capital at home; monopolists suppress wages and undermine the welfare of the working class; and tariffs – in 18th century England – allowed monopolists to protect their monopoly.

The System Today Through Smith’s Eyes

Let’s take a look at the global trading system that we like think of as the fulfillment of Smith’s vision.

- The system tolerates, if not encourages, mercantilism. China, Germany, Japan – all have been, or are, characterized as neo-mercantilist in orientation.

- The U.S. average bound tariff rate is 3.4%. Other countries’ rates are higher, with China at 10% and India around 50%. The lack of reciprocity was not foisted on the United States; the United States agreed to it.

- By allowing critical industries to be offshored, the United States is now dependent on single sources, overseas, for critical national defense materials.

- The main purpose of the global trading system has been to facilitate cross-border flows of capital – the opposite of keeping capital at home.

- Even as capital is able to go wherever it likes, we have no global rules to protect workers against the kind of wage suppression Smith said was inherent to capital.

- The pandemic, and the response to it, are aggravating concentration of economic power, and empowering monopolies. These monopolies are – just as Smith explained – sticking it to workers.

The current rules of globalization have for many years been defended as good for the working class because they have access to cheaper goods. But those arguments fail to take into account the wage stagnation resulting not just from active government and business collusion to suppress wages around the world, but from feckless financiers, who took down the global economy in 1929, and again in 2008. Banker bonuses bounced back – wages didn’t.

WWSD?

What would Smith do? His priority was fighting monopolies to improve the lives of the working class. Tariffs serving monopolistic interests impoverished the working class, and he opposed them.

But what if the elimination of tariffs has been executed in a way that serves monopolistic interests and impoverishes the working class?

We have structured a low-tariff global trading regime to reward capital, not labor. The system is inherently anticompetitive and encourages artificial cost suppression, including wage suppression, as well as supply chain concentration.

Ironically, one of the tools available to correct the anticompetitive nature of the global trading system may well be tariffs.

When Section 201 tariffs loomed on washing machines, foreign producers decided to start producing in the United States. With Section 201 duties on solar, foreign producers decided to start producing in the United States. (In fact, LG Electronics is a common denominator among those investors.) With the Section 232 tariffs on aluminum, a new company revived a shuttered smelter, bringing the number of domestic primary aluminum producers rose from two to three.

As we consider onshoring and ensuring we have surge capacity at home, it is worth considering whether tariffs might actually promote domestic competition, and offset anticompetitive incentives baked into the global trading system. The degree to which tariffs can be effective will depend on a variety of factors, including market structure. But the reflexive hostility to them is worth reexamining.

The anti-tariff crowd will consider tariffs distortive. Distortive of what, though? This line of argument assumes there is some sort of global free market. But there isn’t. The system is already riddled with cost distortions and market failures.

No doubt tariffs are a suboptimal solution. The optimal solution is to have domestic and global systems that promote fair competition. Until we get there, however, tariffs may be a means to the end.

Conservative British MP Jesse Norman penned this balanced essay on Smith, cautioning against reading him as a free market fundamentalist. As Norman explains,

what matters is not the largely empty rhetoric of “free markets”, but the reality of effective competition. And effective competition requires mechanisms that force companies to internalise their own costs and not push them on to others, that bear down on crony capitalism, rent extraction, “insider” vs “outsider” asymmetries of information and power, and political lobbying.

Norman is right. Instead of cherry-picking Adam Smith quotes to promote the empty rhetoric of free markets, let’s appreciate the broader vision Smith laid out. Then maybe we can build a global trading regime that fulfills his true goal – improving the welfare not of monarchs, or monopolists, or merchants, but of the underclass.

August 5, 2020