The recent furor over the NBA, South Park, and the long arm of the Chinese Communist Party is giving the average American a much better understanding of Chinese government authoritarianism in action. Until now, the discussion about the relationship between China and the United States had been dominated by pearl-clutching over how much more dog leashes and frozen tilapia fillets will cost American consumers. The angst over the tariffs has only served to highlight how thoroughly dependent we are on Chinese production.

But what’s been missing from the mainstream discussion is just what that dependence means — including the fact that any such dependence isn’t on China, but on the Chinese Communist Party.

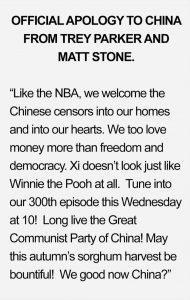

Americans are now starting to appreciate the costs of our plutocracy’s decades-long fetishization of the size of the Chinese market and its plenitude of cheap labor. That blind greed gives the CCP the leverage to stifle the speech of a successful, well-respected American basketball executive, who had the temerity to suggest that freedom is worth fighting for. But it doesn’t give the CCP leverage over people who don’t have blind greed; when they went after South Park, the creators doubled down with a fauxpology. At the heart of the mockery is a sendup of that greed:

The South Park creators aren’t just satirizing business. They’re — unwittingly, perhaps — satirizing the prevailing economic critique of the China tariffs. In an analysis that has gotten more traction than it deserves, one pod of sniffy economists has argued that American “households” will be paying $831 more per year for stuff. For starters, they say the prices are completely passed through at the border – but that doesn’t mean the prices are then passed through from the importer to the household. This:

U.S. purchasers of imports from China must now pay the import tax in addition to the base price. Thus, if a firm (or consumer) is importing goods for $100 a unit from China, a 10 percent tariff will cause the domestic price to rise to $110 per unit.

is just not true. If a firm is importing goods for $100 a unit, a 10 percent tariff may or may not cause the domestic price to rise to $110 per unit. If the importer absorbs the costs into its profits, then the price to the consumer will remain $100 per unit. Testimony before USTR shows that in some cases, this is what’s actually happening.

But that bit of demagoguery isn’t enough. No, the already-flawed number must be bigger. So they factor in the alleged lost efficiency associated with moving these supply chains out of China – what they call a “deadweight loss.” Their calculation of deadweight loss, however, rests on the assumption that China is the most efficient place to produce these goods.

Hello, is anybody home? China is notorious for massive industrial subsidies and currency devaluation, neither of which is necessary if you’re actually the most efficient producer. And if you want to reflect true costs, which is the apparent justification for calculating the deadweight loss, then how about factoring in the costs of suppressed labor rights, environmental degradation, and financial repression? Uh oh – China might be less “efficient” than California.

This sleight-of-hand is an example of the behavior that causes Financial Times editor David Pilling to lament that

we live in a society in which a priesthood of economists, wielding impenetrable mathematical formulas, set the framework for public debate.

Indeed, moving supply chains out of China is the entire point of the tariff exercise. While most trade wonks and media types are focused on the negotiations over Chinese theft of intellectual property (is it theft if you turn it over because you want to make a buck?), the real purpose, reflected in the choice of products subject to the duties, is to frustrate the execution of the Made in China 2025 industrial policy. It’s a policy that threatens to wipe out just about every sector where the United States considers itself to have a manufacturing advantage. As it is, in some cases the United States is dependent on China as a single source of supply for critical materials. That’s a national security problem, one the Pentagon – previously a reliable cheerleader for liberalization — has identified.

And the tariffs are working. Supply chains are moving out of China. It doesn’t matter that they aren’t moving here – that’s not the point. The point is to leave us less dependent on a hostile authoritarian power with grand geopolitical ambitions – a power that has the ability to silence Americans in the United States. The notion of protestors against tyranny being denied a voice, in the very city bearing our first President’s name – a President who voluntarily ceded power to a successor to prove we don’t do monarchy here — says it all.

Dealing with the threat of the CCP was supposed to be the justification for TPP. But TPP’s manufacturing rules are so flawed that it was never going to happen. Even the new NAFTA falls short.

We should absolutely be concerned about the effect of any actual increase in prices on the poor and working class. But it doesn’t follow that the tariffs must be removed. As the economists themselves acknowledge, tariff revenue can be used to provide rebates. If a Republican Congress could get it together to give tax cuts to corporations, why not make the poor and working class whole as a result of any economic burden resulting from the tariffs?

The CCP has done us a favor by showing in very concrete terms how it uses its leverage over us. They know the trade debate in the United States has been governed by econobots who are so obsessed with theory that reality is just something to be manipulated in service of it. But the reality is that not all tariffs are passed on. The reality is that China is not actually the most efficient producer for everything it exports here. The reality is that efficiency isn’t the only thing that matters anyway.

The very thing these economists call a “deadweight loss” — moving supply chains out of China — is what delivers us from the economic clutches of the CCP.

No wonder people are asking whether we can trust economists at all. These particular acolytes of Mammon are supplying analysis that embodies the non-satirical version of the South Park fauxpology:

“We too love money more than freedom and democracy.”

October 10, 2019